This post serves as a “set up” for this blog and all the subject matter we intend to cover. The blog is focused on “ehealth law.” That brings up the question of “what is ehealth law?” It’s not a scientific term; I use it to represent the statutory and regulatory framework that governs health information technology, namely certified EHR technology (“CEHRT”) and other technologies that interact with electronic health information. I divide ehealth law into four areas:

- Health Information Technology Certification (including the ONC Health IT Certification Program, FDA regulation of software as a medical device or the Digital Health Software Pre-certification Program, CMS approval of vendors like registries, e-prescribing, etc);

- Security, privacy, and data rights;

- 21st Century Cures’ prohibition of information blocking;

- Physician payment programs and reimbursement; and,

- Fraud, Waste, and Abuse.

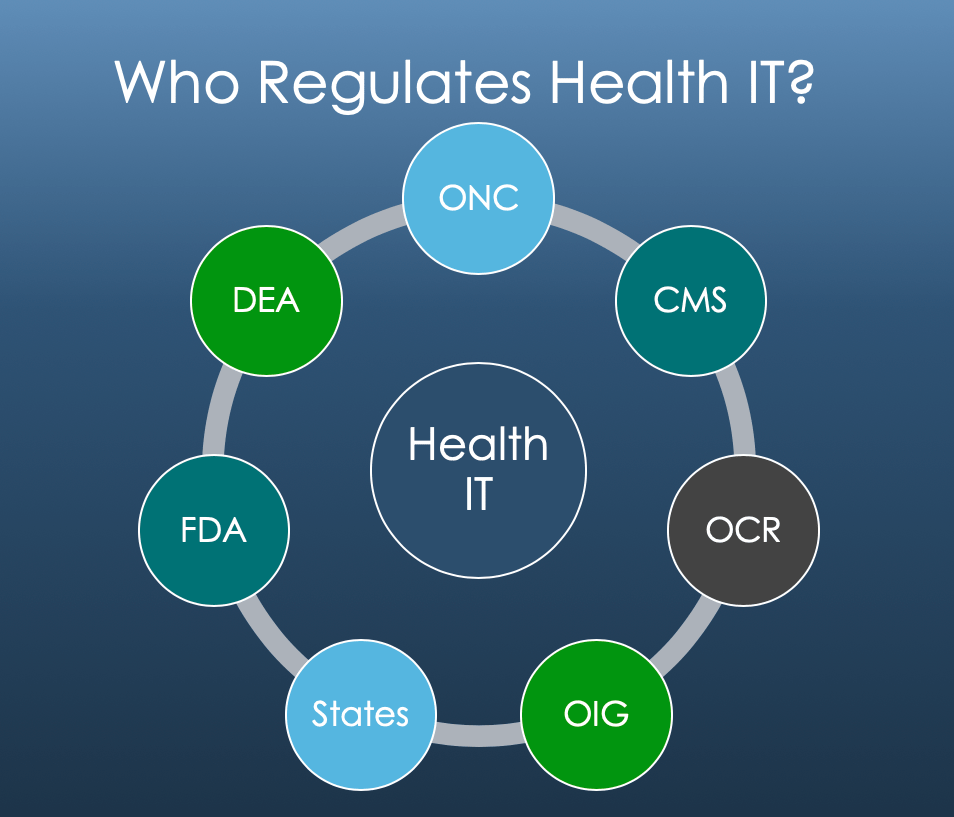

Each of these areas presents different risks to different parts of the healthcare market. Health IT developers take the brunt of all four in equal measure. While they are nominally regulated directly by the ONC, in reality CMS can dictate even development-level decisions by changing their payment program requirements. E-prescribing is regulated by the DEA. The FDA regulates software depending on its use case and design. And because the use of CEHRT is supported by federal tax dollars, healthcare’s fraud, waste, and abuse laws are intrinsically tied throughout the framework from certification attestations to physician payments based on how providers used their technology.

Patient safety is the first, and foremost concern for most healthcare organizations: developers and providers alike. Patient safety is implicated when health IT systems exchange clinical records, submit electronic prescriptions, or offer clinical decision support. Liability can manifest through wrongful death or personal injury claims involving faulty records. That liability can manifest towards a provider directly, a vendor directly, or both jointly depending the facts.

Next, health IT systems are used to submit insurance claims to the government, measure and track quality measures that determine physician reimbursement from the federal government and private carriers, and as preconditions to participation in certain government funded incentive programs (for example, Comprehensive Primary Care Plus). That brings the False Claims Act into play. It not only holds those who submit false claims to the government liable for mere reckless actions, it extends to those who cause such false submissions. Generally, courts read this is as inclusive of any measure or indicator that is material to a government reimbursement decision. This Act presents a tremendous risk to any entity that receives taxpayer funds. A prosecutor only needs to have probable cause that your organization is in possession of information material to a false claim to initiate discovery and an investigation into a company. This is called a civil investigative demand (“CID”). That is a low evidentiary bar, and given the nature of health IT and the data it possesses in its systems, presents a very high and real risk of being investigated even if there is no underlying bad action on the developer’s part. Providers face the same issue. All of this amounts to a high compliance burden and high transactional costs of doing business.

In addition to the FCA, which is civil in nature, the OIG and DOJ have made it clear that they consider that health IT vendors are subject to the Anti-Kickback Statute (“AKS”) (this theory has not been tested in a federal appeals court, yet). What this means is that anybody who receives an Amazon coupon for writing a software review of an EHR vendor is subject to potential AKS and criminal liability. The vendor is liable for the offer; the provider is liable for accepting it. That means health IT developers need to regulate their sales force in a manner similar to pharmaceuticals.

To pile on, now developers and providers must account for 21st Century Cures rulemaking and enforcement in their compliance plans – and how they do business. Information blocking is defined as any practice that “is likely to interfere with, prevent, or materially discourage access, exchange, or use of electronic health information.” If you are a developer, you are liable if you “should know” the practice is information blocking. If you are a provider, you are liable if you do know. 42 USC § 300jj-52(a)(1). With respect to developers then, the bar appears quite low, with providers only moderately more protected. Note, that the practice doesn’t actually have to interfere with the access, exchange, or use of electronic health information, it just has to be likely. Also note, this is very, very broad language.

A violation of this statute can carry up to a $1 million dollar fine for developers. Providers are subject to penalties bundled into CMS payment programs. Both ONC and CMS have proposed rules are that under review with the OMB. The advocacy for and against these rules has been intense because of the stakes associated with them. CNBC recently reported that Epic’s CEO “is urging customers to oppose [these] rules that would make it easier to share medical info[.]” The AMA has noted that it “appreciates ONC’s efforts to address excessive fees” associated with interfaces and interoperability; yet, it expressed concerns regarding the ONC’s proposed timeline for the adoption of CEHRT. These rules touch Medicare conditions of participation, how EHR developers license their technology, how much developers may charge for their services and technology, intellectual property rights, how the products should be coded, among many, many other areas. With respect to developers, that has the potential to radically change (1) how you do business, (2) compliance, and (3) strategic and overall commercial direction of a company.

This is all happening in the backdrop of a preexisting certification and physician payment framework, which carries its own compliance burden. Developers in that space are subject to the technical requirements of ONC certification, must make regular attestations regarding their products’ capabilities, and of course develop updates to their technology on an annual basis to account for changes in CMS payment programs: like quality measure updates in the Merit-based Incentive Payment System (“MIPS”). Furthermore, developers are subject to enforcement actions, called surveillance, by their private sector certifiers ( ONC Accredited Certifying Bodies) and the ONC itself. The certifiers, ONC and OIG will all ultimately end up playing key roles in the enforcement of 21st Century Cures’ prohibition of information blocking as well.

This blog is going to cover these subjects, and how developers, providers, and others can protect themselves and minimize their risk. All of these are subject to regular rulemaking and change year-to-year. Our next couple of posts will cover the new proposed Federal Health IT Strategic Plan (which unsurprisingly focuses on interoperability) and what it means directionally for the healthcare industry. And as the proposed 21st Century Cures rules are finalized, we’ll unpack the requirements and provide some insight into what they mean operationally.

One thought on “The Regulatory & Enforcement Framework for Health Information Technology”